Progesterone governs many important processes occurring in a woman's body, including menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause. Yet, most women don't understand the exact mechanisms behind progesterone production.

Continue reading to learn more about progesterone production, including the hormone's glands, receptors, and flow within the body, in order to have a more broad understanding of its crucial role in women.

Progesterone Production

Why is Progesterone Produced?

Progesterone is a vital hormone for the menstrual cycle and pregnancy.

The hormone's major responsibility it to thicken the endometrial lining in preparation to nourish an egg in case conception has occurred.

After conception, progesterone helps establish the placenta; stimulates development of breast tissues; prevents lactation; and strengthens pelvic walls in preparation for giving birth.

Even after reproductive years, progesterone will still be produced, but the hormone will acquire different roles in effort to maintain a healthy hormonal balance.

Where is Progesterone Produced?

In the follicular phase preceding ovulation, the majority of progesterone is produced by the adrenal glands. It is reported that the contribution of the ovaries to the blood plasma levels of progesterone is small during this phase of the menstrual cycle.

However, during the luteal phase following ovulation, a large amount of progesterone is produced in the ovaries, coming from the corpus luteum.

The corpus luteum continues its production throughout the entirety of the second half of the menstrual cycle. Then, the structure dissipates in time for the new menstrual cycle to begin if a woman's egg is not fertilized.

If the egg is fertilized, progesterone production will transition to specialized cells of the placenta. In late pregnancy, it is believed that the hormone's production consumes an amount of cholesterol equivalent to about 25% of the daily turnover in a healthy woman who is not pregnant.

Once a woman enters perimenopause and begins to experience anovulatory cycles, lower levels of progesterone are produced in the ovaries with more being produced in other organs, such as the adrenal glands.

Aside from aforementioned organs, smaller concentrations of progesterone are also produced in peripheral nerves and brain cells.

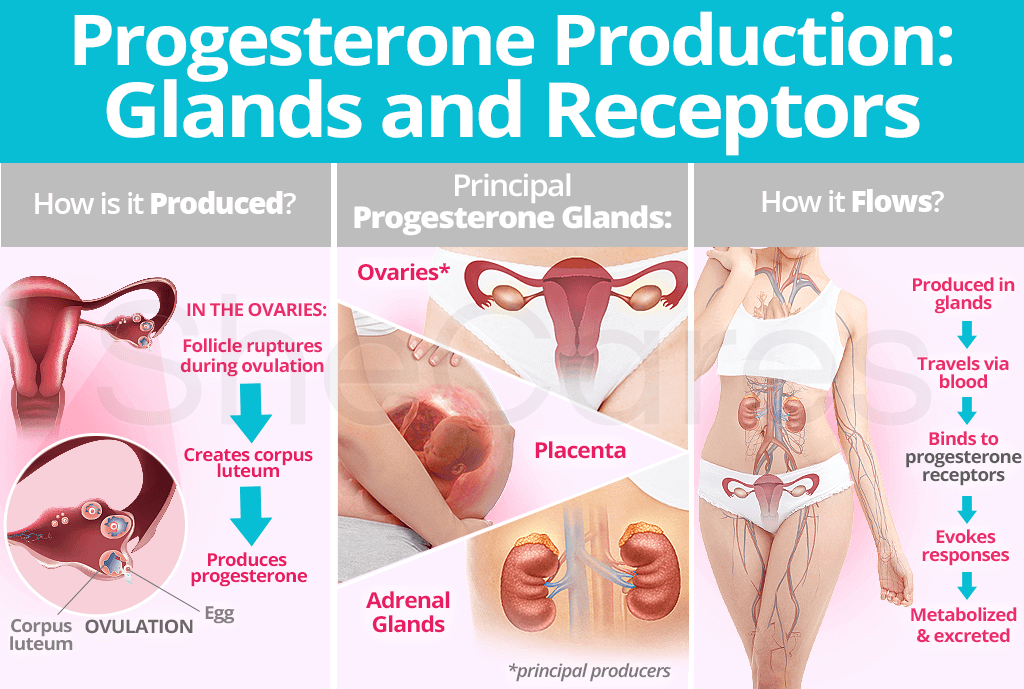

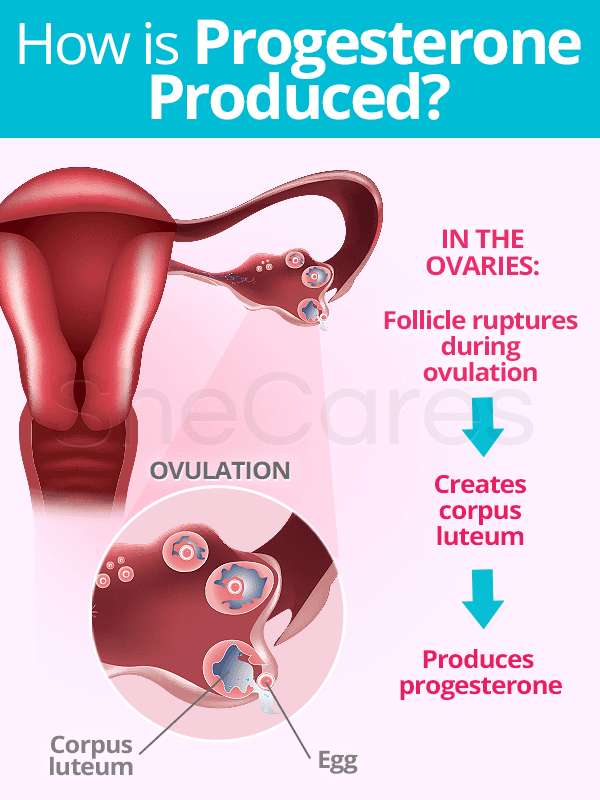

How is Progesterone Produced?

Progesterone is produced by the remnants of the ovarian follicle - the corpus luteum - after ovulation and throughout the duration of the luteal phase.

Also, progesterone is continually produced if fertilization occurs. The developing embryo will release human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) hormone to signal extended progesterone production from the corpus luteum until the placenta takes over.

Measurements of the hormone in ovarian blood demonstrate that the corpus luteum remains functional throughout most of the first trimester. Before the decline of luteal functions, placental production of progesterone becomes adequate enough to maintain pregnancy.

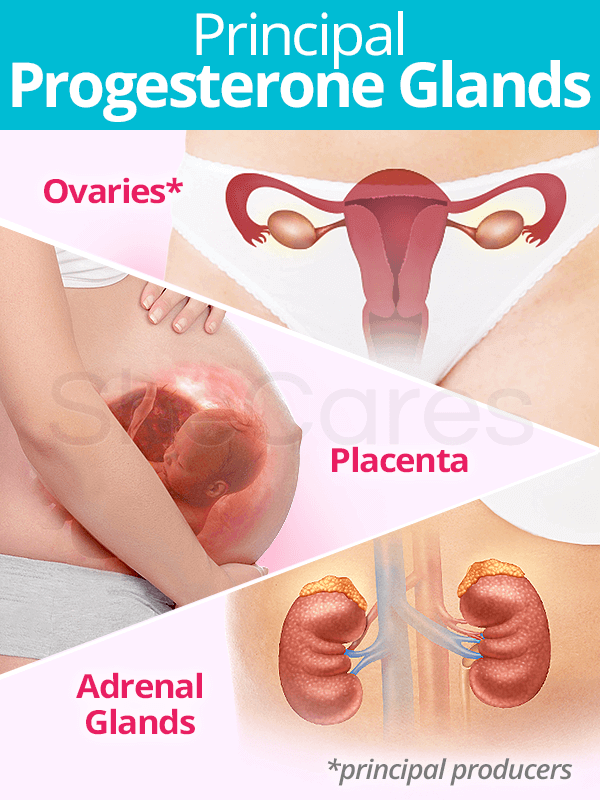

Progesterone Glands

The major glands producing progesterone are the ovaries, adrenal glands, and placenta. From these, the hormone is secreted for use within the same glands or released to other areas of the body.

In the first half of the menstrual cycle, the adrenal cortex produces and secretes progesterone. This is done by the extraglandular conversion of adrenal pregnenolone and pregnenolone sulfate into progesterone.

Before ovulation, the adrenal glands and ovaries each contribute about 50% of total progesterone production.

However, the ovaries are a significant gland as progesterone created from the corpus luteum is used to build up the uterine lining.

In pregnant women, this production will eventually decline until the placenta takes over production. The placenta converts cholesterol to pregnenolone before being converted to progesterone.

All of the pregnenolone produced is either secreted as progesterone or exported to the fetal adrenal glands for further steroidogenesis, a process in which steroids are converted from cholesterol and changed into other steroids.

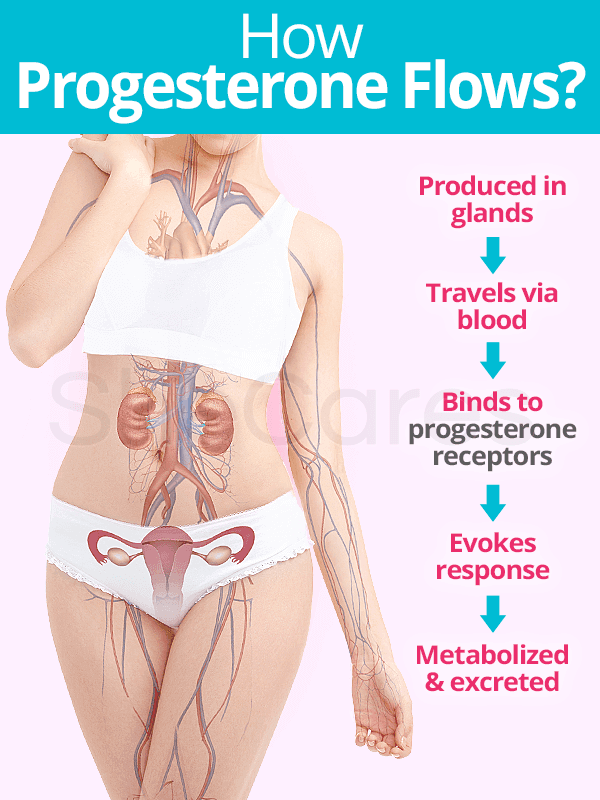

Progesterone Flow

Flow of Progesterone in the Body

Once produced and secreted, progesterone is transported throughout the body in the bloodstream, binding to specific hormone receptor sites and influencing cell behavior.

Because progesterone hormones impact a range of targets and receptors are found on a variety of tissues, an imbalance affects not only a woman's breasts and uterus, but the brain, nervous system, cardiovascular system, and more.

Progesterone Receptors

Once cell receptors receive messages from progesterone hormones in the blood, a variety of responses will be generated as instructed.

It is important to note that progesterone receptors can also act as target cells for many other regulatory molecules. For instance, breast, bone, and uterine cells that react to progesterone hormones can accept messages from estrogen and androgen hormones.

Progesterone Excretion

Similar to estrogen, the metabolism of progesterone takes place mainly in the liver. It is here that progesterone metabolites are conjugated and then subsequently excreted in urine.

Other organs contributing to progesterone metabolism are the brain, kidneys, endometrium, myometrium, and mammary gland.

High progesterone levels or reabsorption of progesterone back into the body can occur if the excretion process malfunctions. This, consequently, evokes a hormonal imbalance, causing a myriad of symptoms.

Nonetheless, even though most people associate progesterone with its functions in the female reproductive system, the hormone has a variety of other roles. Continue reading to learn more extensive information about progesterone roles and effects in the body.

Sources

- Breastcancer.org. (2017). Understanding Hormone Receptors and What They Do. Retrieved September 9, 2019, from http://www.breastcancer.org/symptoms/diagnosis/hormone_status/understanding

- Brinton, R.D. et al. (2008). Progesterone receptors: form and function in brain. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 29(2), 313-339. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.02.001

- Hites, R.A. (1992). Handbook of Mass Spectra of Environmental Contaminants. Florida: Lewis Publishers. Available from Google Books.

- Johnson, L. R. (Ed.). (2003). Essential Medical Physiology. USA: Elsevier. Available from Google Books.

- Lobo, R.A. et al. (Eds.). (2000). Menopause: Biology and Pathobiology. USA: Academic Press. Available from Google Books.

- McCance, K.L. & Huether, S.E. (2014). Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults and Children. Missouri: Elsevier. Available from Google Books.

- Mesen, T.B. & Young, S.L. (2015). Progesterone and the Luteal Phase. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, 42(1), 135-151. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2014.10.003

- Society of Endocrinology. (2015). Progesterone. Retrieved September 9, 2019, from http://www.yourhormones.info/Hormones/Progesterone.aspx

- Tulane University. (n.d.). Endocrine System: Types of Hormones. Retrieved September 9, 2019, from http://e.hormone.tulane.edu/learning/types-of-hormones.html